Time(bound), Material(bound): A review by Ruby Constance of SPACE(BOUND) at GalleryGallery

10th - 31st July 2021

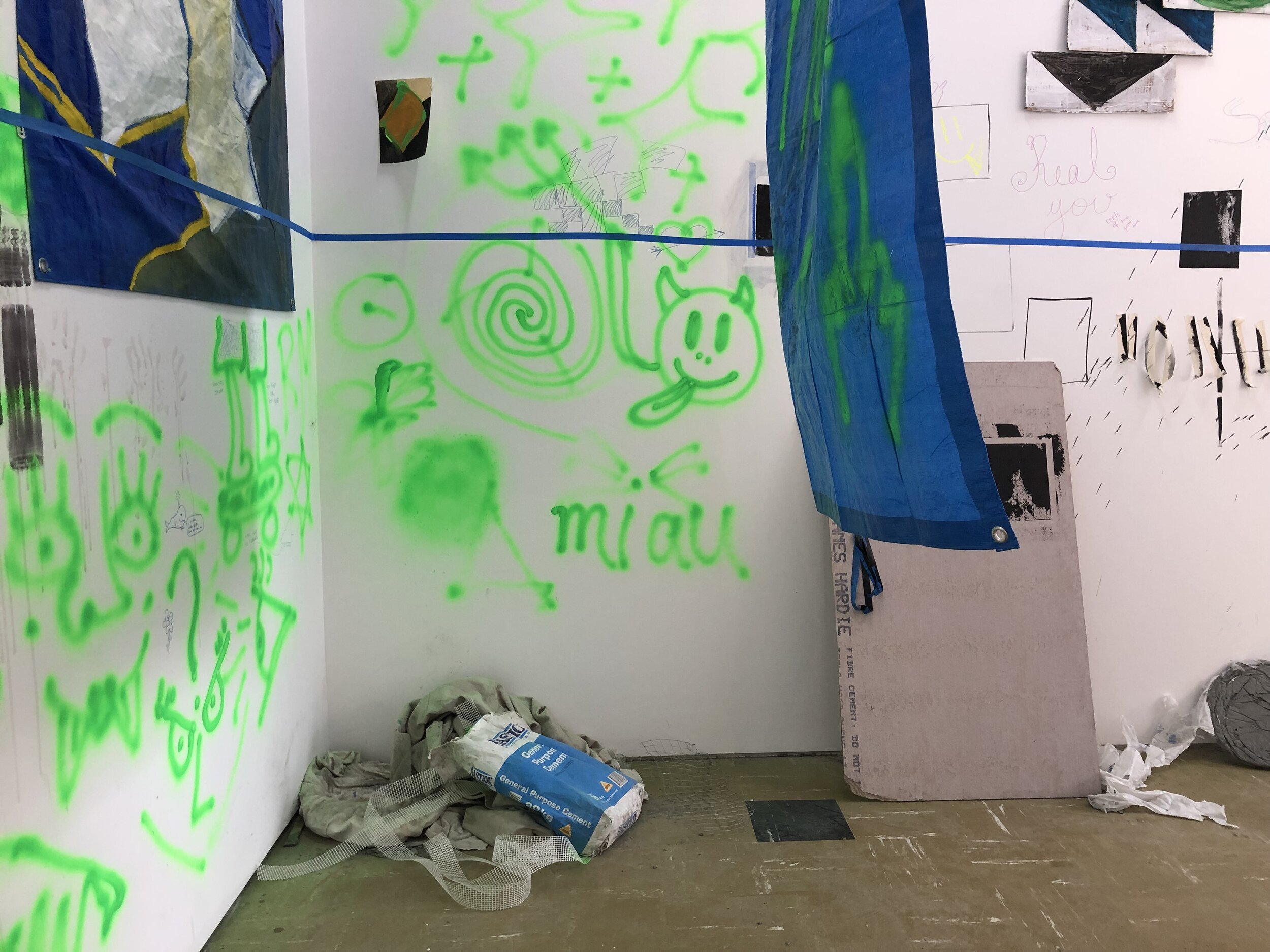

Space(bound) is a collaborative and interactive project by RMIT honours students Tamar Gordon, Aaron Ashwood and Lauren Fahey who spent several weeks inhabiting the GalleryGallery space and constructing an environment within it. Materials include items sourced from and inspired by construction sites, elements from the artists’ personal art practices and university assessments, and the detritus of their lodging within the space such as takeout boxes (plus chopsticks) and beer bottles (Furphy’s). The contents could be described overall as trash-art shifting into assemblage, site-specific, installation, and collaboration, should we feel compelled to situate it in the context of art history. There were two parts to this exhibition that I will look at separately: the physical and sculptural enterprise that the artists themselves installed, and then the collaborative element they introduced on the opening night.

In the artists’ created environment, blue tarp and conjoined fabrics hang from the ceiling. The walls are plastered with miscellanea, dominated by a collection of cardboard slices painted with primary-coloured geometrics. There is a ‘pedestrians ahead’ sign, a detour sign, and in the middle of the room there is a metal shelf that looks like the victim of some immense violence, dramatically twisting and leaning into space. This shape is contrasted by a curving meander of crushed aluminium which snakes through it and turns it into a surprisingly lovely sculptural form. Upon this shelf sits various paper refuse along with the takeout box (chopsticks). The shelf is rigorously sticky-taped to some other hard-to-identify pieces of scrap furniture, and a striped black and yellow pole pokes from this centrepiece adorned with a thick red rubber glove.

A visual theme of repurposed construction elements lends a charming coherence to the environment, with its yellow-and-black, its moments of concrete, its paintings of traffic cones. ‘wo/men were at work in this space’ a sign could read, or ‘wo/men were at work in this space industriously repurposing notions of ‘work’ into this diligently manifested yet playfully improvised landscape’. There is a lovely interplay between the artists’ clear labouring over certain parts, such as the tapestry of different fabrics that hangs at measured angles across the space, and the untouched yet arranged ‘scrap’ elements. These treatments allow unexpected aesthetic appreciations to emerge, highlighting the sculptural promise of forms such as those found in hard rubbish.

There are no obfuscations of process and there is an honesty, a transparency here which is charming. The human touch is intelligible, as is the human care.

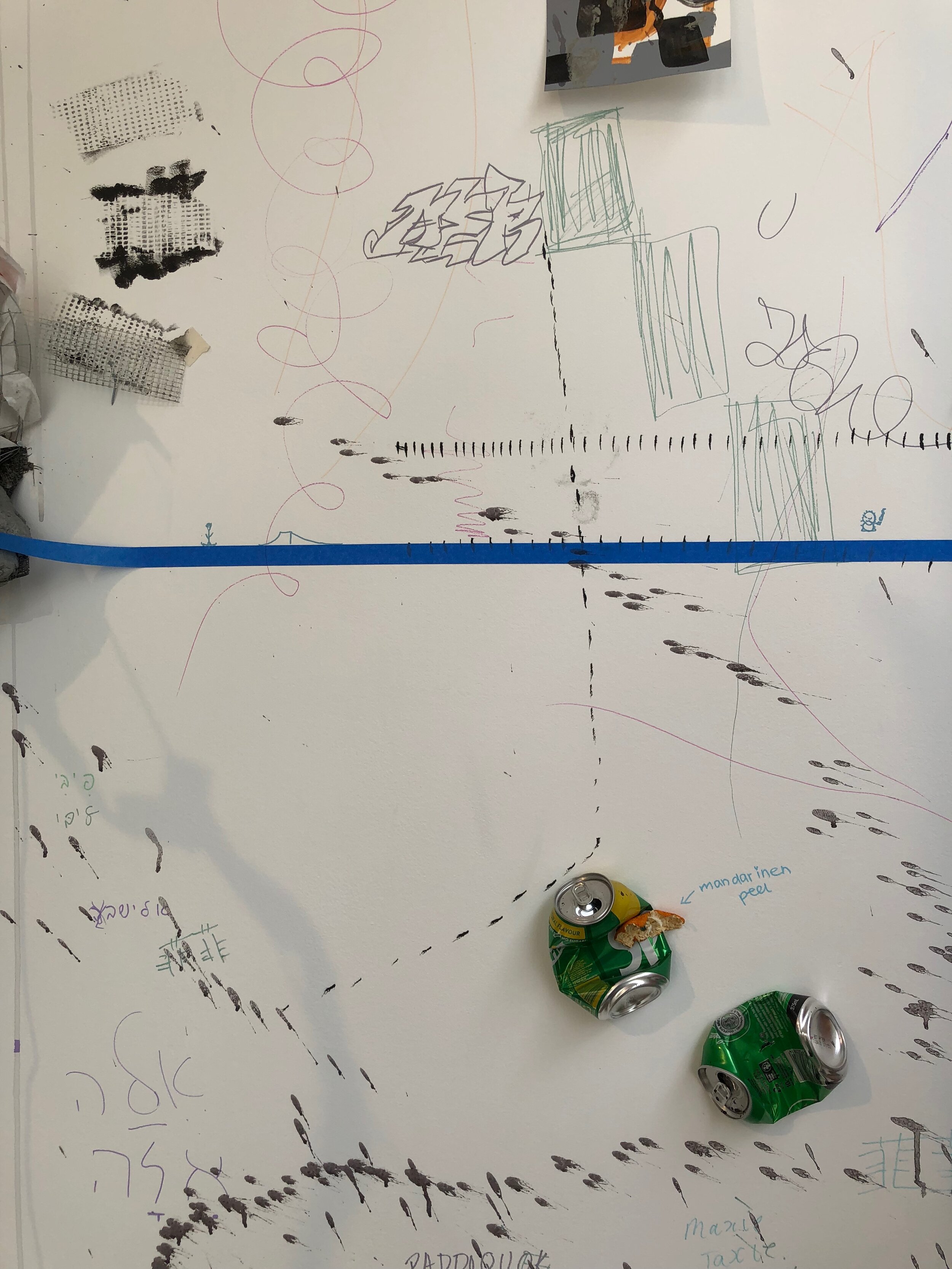

On the opening night of July 10th the artists let the audience go to town on the space themselves. Participants adorned the walls with an orgiastic amount of cheap texta and bright-green spray paint. They spilled much ink from a weed-sprayer across the floor, frolicked in tinfoil and tape, and added to the trash-art objects with their own personal and party rubbish including an Officeworks print card (floating angelically upon a hammock of sticky-tape), beer cans (Cooper’s Green) and a tobacco pouch (empty).

Post-opening, authorship and intention are somewhat blurred in the sculptural elements of the work. This is an interesting dynamic, in the artists’ willingness to let themselves be partly, or wholly, obscured, a practice in ego-dissolution perhaps, in preciousness and un-preciousness. Authorship is less obscured in places where the time-bound and material-bound nature was clear, such as in the masses of cheap texta drawings and writings which clutter the original elements.

In the short and sweet didactic panel description outside the gallery door the artists stated how they had ‘inhabited the space as their own’ and had ‘assembled, played, documented and archived’ within it, inviting the viewers at the opening to ‘move things around’ and ‘change the space and play through the entirety of the evening.’ Though the event was framed in this gentle and considered language of ‘play,’ the reactive participants simply did not have the investment from languid weeks spent painstakingly arranging the space, considering aesthetic alternatives, and exploring visual and spatial potential that the artists were afforded. On the exhibition opening the public seemed less to develop the aesthetic form of its environment rather than deface it, and this is where the incongruity of the communal participation lies.

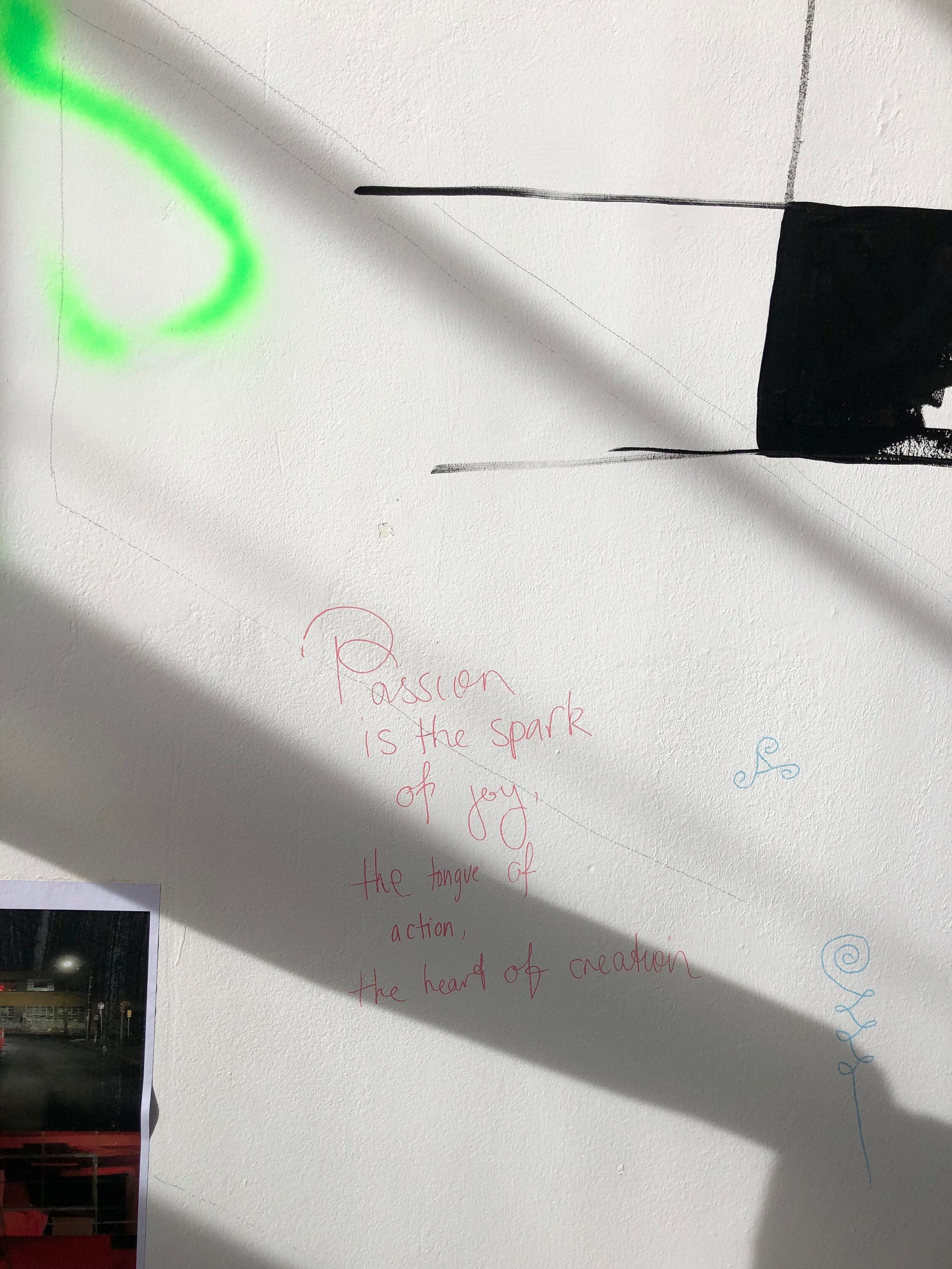

A cacophony of cheap textas was the most accessible material provided, initiating a widespread text/graffiti element to the work. Though this effect was interesting in its own right, one can’t help but feel that these materials were a bit of an afterthought in terms of their cohesion with the already present forms. Perhaps the text seems to struggle slightly to locate itself as the ‘play’ in the sculptural sense that the artists’ exhibition description led one to believe they had intended; it resembles instead the thoughtless, profane scribblings of adolescents slightly too high on the transgressive thrill of drawing on a gallery wall to consider things such as ‘environment’ or ‘aesthetics.’

The main interest to this element is the random associations in the language, if one appreciates things like that, which I do. The eye inevitably drawing itself to text, visitors found it of interest and perfectly natural to meander along the walls following these doodles. Unfortunately, this enticing legibility acted as a distraction from the sculpted environment itself that the artists had laboured over to assemble.

This is not to undermine all the materials made handy. There was bright green spray paint, a weed killer/watery ink dispenser, sticky-tape, foil, reams of paper, and whatever the participants felt game to part with (largely, empty beer cans). The artists had, in their defence, highlighted in their description/invitation that the whole place was up for intervention, and interventions were duly made: much tape was dispensed, the hanging blue tarp was illustrated in spray paint, and the mouldy pizza slice was nailed to the wall. We cannot be said to be bereft of interventions.

Curious about the intended primary location of the art and whether the focus was on the sculptural elements or on the opening night’s participatory activities, I asked the artists after the fact to point me towards the best use of my attention. They shared with me that the focus of the project was on their own weeks spent cohabitating in the gallery, which I found satisfactory, as I too felt the true warmth and interest emanated from their own movements and arrangements in the space. However, the choice to give the environment a half-life in the hands of its visitors— instead of ending its development at the end of their habitation, which could easily have happened— meant the volatile, unpredictable participatory element was felt and understood to be an extension of the work, and necessitated it to be analysed as such.

One can’t help but wonder: what if the only materials presented to the participants were needles, thread, and fabric? Would it have prompted a quiet sewing circle, where people were forced to consider their aesthetic intention before deciding to doodle a hairy ball sack? What if the materials presented were even more masses of yet to be sculpted trash materials, with found objects and paint and staple guns and so forth, so that they could add to the existing sculptural elements in a seamless fashion and truly push the questions around authorship of the artist, of everybody-as-artist, of breaking down the artist/viewer dichotomy?

These would be the patronisingly prescriptive questions had the artists specified the opening night shenanigans as the site of the artwork, which they did not; these questions do, however, pose the necessity for a thorough consideration of every element of experiential art. Particularly if it is dipping into interactive territory, unless the intention and instructions to the audience are rigorously designed and fool-proofed beforehand, there are simply so many unknown variables that can create unplanned discourses and veer a project from its focus. ‘Throwing an art piece to the elements and into a collaborative context after the fact’ is, though fun, hardly a gripping thesis when not backed by the same thoughtful level of intimate intention and detail the artists applied to their own stay within the space.

What it amounted to for the artists was though, perhaps, just that: the exhilarating act of throwing one’s work, and symbolically oneself, to the gleeful mob. ‘Please deface what I have done in whatever way you see fit,’ the viewers could easily have heard from the booze at hand and the mass of coloured textas. And indeed, there was a liberatory feeling in this gesture, like the gallery was providing a boundless Eden within which this rare lightness could take place. In those terms— of glee, freedom, and adolescent transgression— the exhibition opening fulfilled its goals. The installation itself— operating within the quite different frameworks of playful intention, experimentation, and the potentialities of repurposing overlooked trash-art elements into engaging environments— also fulfilled its goals, though its quiet victories were perhaps overshadowed.

Ruby Constance

Images supplied by the artists.